Sometime in the fall of 2020, after my husband built a set of stairs with his father and replaced the carpet in our rental apartment (yes, in a rental… I insisted) with laminate wood flooring, his TikTok algorithm began to steer him towards construction accounts. Men in hard hats and bright yellow vests talked to their front-facing cameras or to a coworker, detailing the ins and outs of a typical day, or letting off steam after a particularly difficult shift. My husband kept watching as TikTok led him through an algorithmic parade of men with blue-collar jobs, eventually ending up on what I called “tugtok,” a community of tugboat operators filming “day in the life” videos, wind rippling through the audio or rain pelting the camera as they stood onshore or at the helm of a boat.

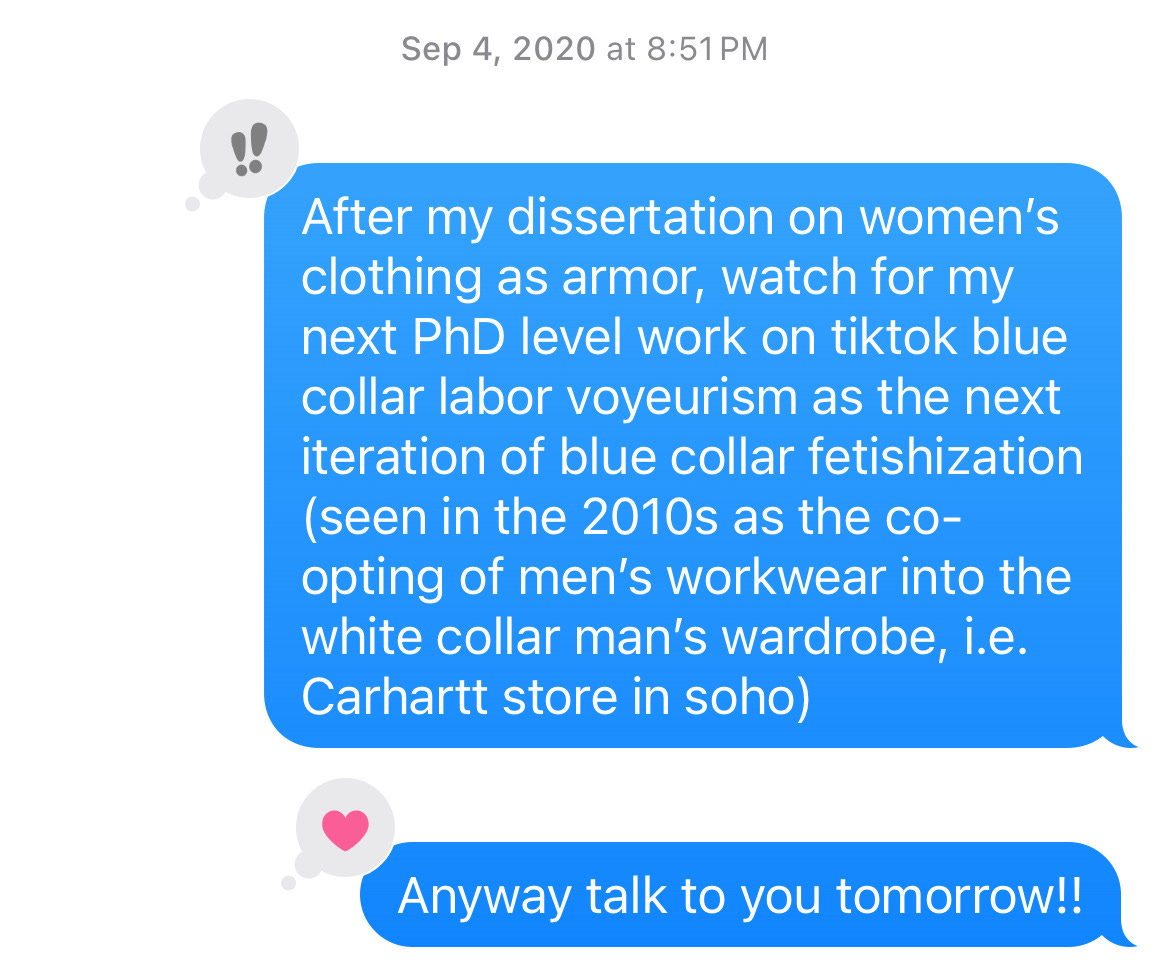

Tugtok, and every video that preceded it, activated a curiosity that had lain dormant in my brain after a decade’s worth of people-watching in lower Manhattan. That newly reactivated curiosity eventually prompted this text to my friend Camille, who has for years graciously allowed our text message chain to act as a receptacle for many a tangent or half-baked theory.

Then

posted this, and it reawakened that line of thought.Why are those of us who have never worked on a construction site, or a farm, or a factory line so drawn to “traditional” workwear?

Of course, this isn’t a new idea. If you’ve been anywhere even Instagram-adjacent in the last ten years, you’ve seen the memes. Perhaps you’ve even rolled your eyes at a man in a Carhartt beanie or coveralls on a laptop at a coffeeshop, or given a sideways glance at the crowd in the Soho Carhartt WIP store, which expanded into an even bigger neighboring space a couple years ago.

Our obsession with workwear goes back much further than 2010s New York—it’s baked into American culture. Jeans are now almost completely divorced from their origins as workwear (I’ll leave you to read up on that on your own time, as many talented writers, including Levi Strauss & Co.’s former historian, Lynn Downey, have delved into the history of denim), and buying field jackets at army-navy stores has almost become a rite of passage for those in the punk and counterculture scenes1.

But in the 2010s, every brand wanted in. Not only were people buying clothes from classic heritage brands like Carhartt and Dickies, but mall fashion and DTC brands began putting out their own spins on workwear. Companies like Everlane and Madewell, geared toward the “young professional,” sold their own versions of chore jackets, utility jumpsuits, overalls, work boots, pants with reinforced knees… even some indie brands of Instagram notoriety got into it (the Rudy Jude utility pant, the Curator SF painter pant, the LF Markey boiler suit).

I’m not immune! I’ve owned more than one of the garments above, and I’d have the Rudy Jude pants too if I had the money. But it’s good to step back and examine why this type of garment is so appealing.

The least generous interpretation of this fascination is as a form of snobbery, a snarky in-joke, subversive only because of how obviously it contrasts with the rest of your outfit’s cultural and sartorial signifiers. Then comes a more neutral, anthropological reason: workwear as an extension of Americana, a (perhaps condescending) attempt to feel commonality with a group you may not otherwise have much in common with.

There are, of course, jobs and tasks that aren’t considered typical blue-collar work—creative work like painting and sculpting, care work like babysitting or nannying—that naturally lend themselves to a wardrobe that can take a beating.

But even for those who will never get their hands dirty (literally) as a part of their job, I think there’s something bigger here. My most generous explanation is that we reach for these type of garments because we are longing for stability. Workwear is a sartorial symbol of “simpler” times, a reminder of a time when economic upward mobility was more common2, when a blue-collar job could provide an ample salary for an entire family3.

In times of global precarity and uncertainty, at companies that seem to lay off workers year round, it makes sense that even those of us in “knowledge” work, in “creative” jobs4, in bullshit jobs5, in remote jobs, in jobs that require a college degree, would reach for the durable over the ephemeral—tough canvas over a diaphanous silk shirt or a flimsy fast fashion dress designed to fall apart within a year.6

There’s also a very practical reason to turn towards the durable. This shift in taste was happening alongside the growth and proliferation of sustainable, ‘slow fashion’ brands, like Ilana Kohn (2012), Elizabeth Suzann (2013), and Rudy Jude (2016), etc. Yes, the Rudy Jude utility pants are expensive, but the trade-off was the knowledge that you were supporting a small business whose clothes were made from sustainably sourced fabric, plant-dyed, and sewn in the US.7

Wearing these brands became a signal in certain communities that you were interested in sustainability, that you were willing to spend more money for clothes that would last longer than a season. It makes sense that awareness and growth of sustainable fashion brands grew in parallel to mainstream interest in traditional workwear—both concepts are rare signifiers of durability, something tangible to latch onto in an era of general disconnect from the origins of the products we consume.

Appreciation to appropriation (culture, class, etc.) is a gradient, and I don’t think wearing workwear automatically lands you on the appropriation side of that scale. But I do think it’s important to individually examine why we are drawn to the garments we wear, and where that desire comes from. Knowing your history and the context in which your clothing exists and is interpreted is just another form of power.

(Thanks to for her suggestions and assistance with the title!)

For white people. Upward economic mobility has always been more difficult for BIPOC people in the United States, though there tends to be more research on race and economic mobility in the US focused on the differences between white households versus Black households than research inclusive of multiple races and ethnicities.

I put these descriptors in quotes because there are few jobs inherently more creative or demanding of specific knowledge than construction jobs, yet those jobs are rarely ever referred to as creative work or knowledge work. I recommend reading Building: A Carpenter’s Notes on Life & the Art of Good Work by Mark Ellison.

Another recommended read: Bullshit Jobs: A Theory by David Graeber. Thank you, David Graeber, for all you did—RIP!

(There’s also the reality that wearing stereotypically masculine garb as an otherwise femme-presenting person can offer protection or invisibility by deflecting male attention, but as I mentioned in the text exchange above, that’s a whole other dissertation.)

I ATE this up! I LOVE your anthropological generosity here re: stability and I think you’re really onto something.

was talking to a friend the other day about how what looked like happy times and stability back then - a home and garden to eat from, kids running around the neighborhood with dirty feet, etc might look like what some consider “abject poverty “ today! yet we live in a culture where the “dream” points towards the upward trajectory of wealth (and bullshit jobs? 😂) while simultaneously grieving that community and simplicity of that past (and cosplaying it)

was so happy to see David graeber mentioned here too. rest in power + peace

Omg this is so good! I have wondered abt this as well. You got me thinking: is it the ultimate luxury nowadays to be able to do some type of work with hands, outside, building stuff? Like the Rudy Jude family—they build those dream houses and kayak etc, like is that the ultimate luxury that few can ever achieve? I’m also thinking of all the yoga teacher types I’ve encountered in nyc who get into such lines of work AFTER working in finance, law, advertising. They burnout but made enough money to move into something more ‘hands on.’ Like the people who start all the millennial coded food stuff. They all seem to be of a certain, upper class.