We all need to give Joan Didion some space. I’m serious. We’ve had the documentary, the adulatory style features and thinkpieces, the auctioning off of her possessions… we do not need her journals! Let this woman rest in peace!

I find Didion’s writing just as elegant and captivating as anyone else, but the fascination with her aesthetic is particularly puzzling to me because there are plenty of iconic New York City writers of and around that era whose style is just as interesting. One of those writers—less famous, but just as deserving of attention—is Laurie Colwin.

Through my ‘books read 2012’ Google Doc, I can trace the path I took through Colwin’s work—after The Lone Pilgrim (a gift from my mom), I read Home Cooking (a book of essays, where I first encountered her concept of the ‘domestic sensualist’). Then I went on to the next collection and the next novel and the follow-up essay collection and on and on until I’d finished all of her published works within the first half of the year. I read greedily, as if there would always be more. And then I Googled her. Laurie Colwin died in 1992 of an aortic aneurysm at age 48, leaving behind a husband and an eight-year-old child.

"Oh, domesticity! The wonder of dinner plates and cream pitchers. You know your friends by their ornaments. You want everything. If Mrs. A. has her mama's old jelly mold, you want one too, and everything else that goes with it—the family, the tradition, the years of having jelly molded in it. We domestic sensualists live in a state of longing, no matter how comfortable our own places are."

— from The Lone Pilgrim

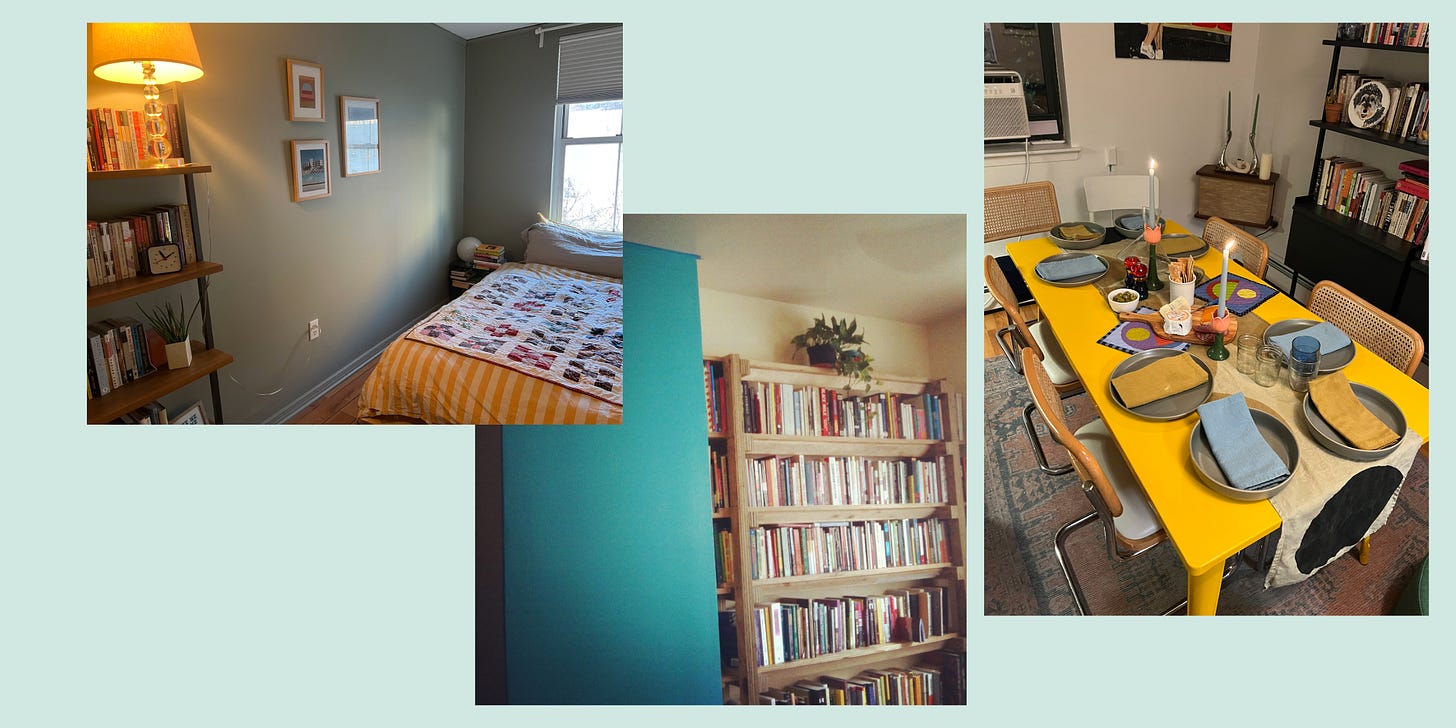

The concept of domestic sensualism is one of Laurie Colwin’s enduring legacies—but what exactly is it? I think of domestic sensualism as the deep, personal pleasure found in the rhythms of daily life. Sensual in the sense that it’s rooted in sensory details—texture, scent, and warmth. Colwin’s domestic sensualism is warm, imperfect, and lived-in, a benign chaos. It’s not about perfection or aspiration but rather the quiet, tactile pleasure (and the continuous work) of making a home. I see it now as an antidote to the pernicious strain of minimalism omnipresent in Architectural Digest YouTube tours, those spaces designed only to be seen, not touched.

Colwin’s books are ripe (sorry) with descriptions of meals and homes that conjure up the vibe of domestic sensualism:

“At each place was a juice glass, a coffee cup, and one of Wendy’s breakfast plates, which were decorated with pheasants and cornflowers. All juice was squeezed fresh: Henry, Sr., believed that harmful metals leached into juice from cans, and also that liquid must never come into contact with paraffin, as in waxed cartons. The whole family backed him on this point, and everyone was happy to take turns squeezing oranges and grapefruits in the old-fashioned squeezer.”

—from Family Happiness

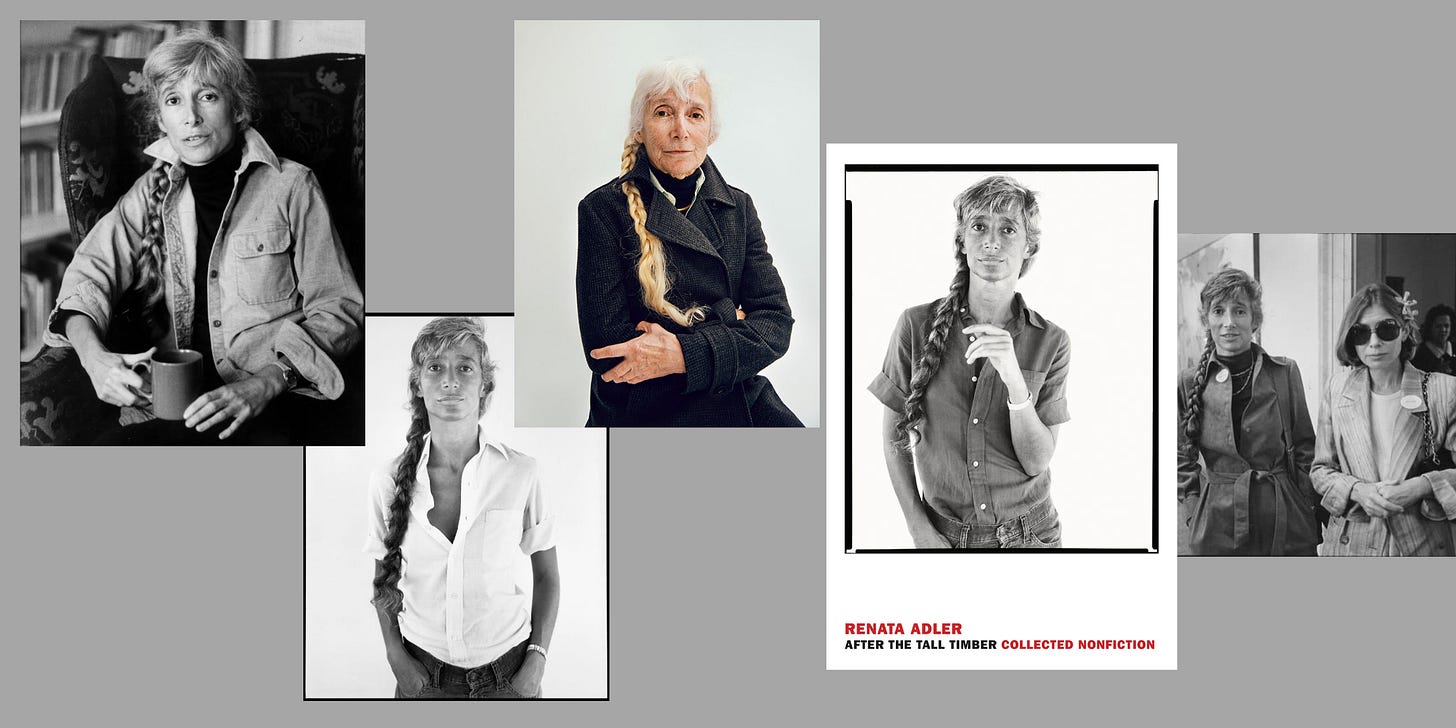

But this identity as a domestic sensualist extends beyond the confines of the kitchen—you can also see it in Colwin’s personal style. There’s a unified aesthetic to her wardrobe, simple yet considered, similar to the way she dressed her characters. If she’s not wearing a collared shirt, you’ll likely find her in a striped t-shirt or a simple rollneck sweater. (I can almost guarantee that Laurie Colwin cared about natural fibers, I just have a feeling...) She also owned and wore multiple overall dresses/jumpers. Aside from one colorful beaded necklace, her jewelry was simple: small hoop earrings, a flat-link gold chain. More often than not, her sleeves are pushed up to the elbow, suggesting a certain readiness, an openness to spontaneity. Deciding on a whim to have ten people over for dinner in your tiny apartment? No problem. She’s ready to go.

“Should friends call at the last minute and say they are coming by, you might—if you are truly unhinged—make an evening of it.”

— from More Home Cooking

In most of the publicly available photos of Colwin in her later years, she is wearing a simple black wristwatch, an unanswered plea for just a little more time—a tiny, devastating detail not unlike something she would have written. Take this paragraph from Shine On, Bright and Dangerous Object, where a young widow who has been reckoning with her husband’s past infidelities describes a woman who may have known him:

“Her style was so particular it made you feel you knew something about her. Everything she wore looked like the only one of its kind: her skirts were embroidered, her blouses were monogrammed, her sweaters were crocheted, and her shoes from year to year were the sort of shoes you thought they weren’t making anymore. If you asked her where she got any of her clothing, she would tell you the name of the shop and how many years ago it had gone out of business. She was immaculate and nothing she owned was new; her touch on things was so light it looked as if everything she had would last forever.”

Or this passage from A Big Storm Knocked It Over, where a newly married woman considers whether or not she presents differently after her wedding:

“She wore plain, trim clothes: she liked her skirts short and her sweaters large. For jewelry she wore a large gold man’s watch that had belonged to her late father—she had snagged it before her older sister, Nora, got it first—and she wore a Navajo silver bracelet with one round turquoise, and a plain brass bracelet, both presents from Teddy.”

For me, domestic sensualism means caring about the stories and the origins of everything I own, remembering where things came from, whether that’s clothing or any of my other possessions. Knowing that the coat I’m wearing or the scarf I’m wrapping around my neck has been with me for many versions of my life so far. Taking pleasure in my clothes and books and knickknacks because I have amassed a collection of items through which it is possible to learn something about me. Wearing my favorite clothes even when I’m working from home, because they deserve to be worn. Inviting far too many people over for dinner and insisting on using cloth napkins and making three desserts. Framing my friends’ artwork and hanging it all around the apartment. Being able to say “I got this on Craiglist” or “I found this on a stoop” or “I hunted down this specific vintage ceramic sugar bowl on eBay for months.” My pride isn’t solely in ownership, but also in origin and usage. Laurie Colwin is probably responsible for fine-tuning the way I appreciate and care for everything I own.

Laurie Colwin would have turned 81 this year if she were still alive. I can’t bear to think of all the books she still could have written, of the body of work we might have been lucky enough to enjoy had she lived as long as Didion. I do think Colwin would have encouraged the greedy pace at which I devoured her oeuvre. There’s an air of domestic sensualism to the idea of spending an entire day on the couch with a stack of books beside you. Like many of my favorite on and off the page heroines (Bridget Jones, Maria Von Trapp, etc.), Colwin wasn’t the type to deprive herself of pleasure just because she thought she should. In this way, Colwin is almost the polar opposite of Didion, who seemed to live by a self-imposed asceticism that would put many a monk to shame.

Didion’s various homes and apartments actually look like they have more in common with Colwin’s than those spare, whitewashed spaces—there are piles of books, terra cotta tiles, paintings and colorful shelving. But Didion herself at home is a dangling cigarette, an arm stretched languidly over the back of a couch, a domestic stillness or stiffness, rather than a sensuality. In the photographs we have of Colwin, she looks confident, comfortable, engaged. Laurie Colwin always looked like she was living.

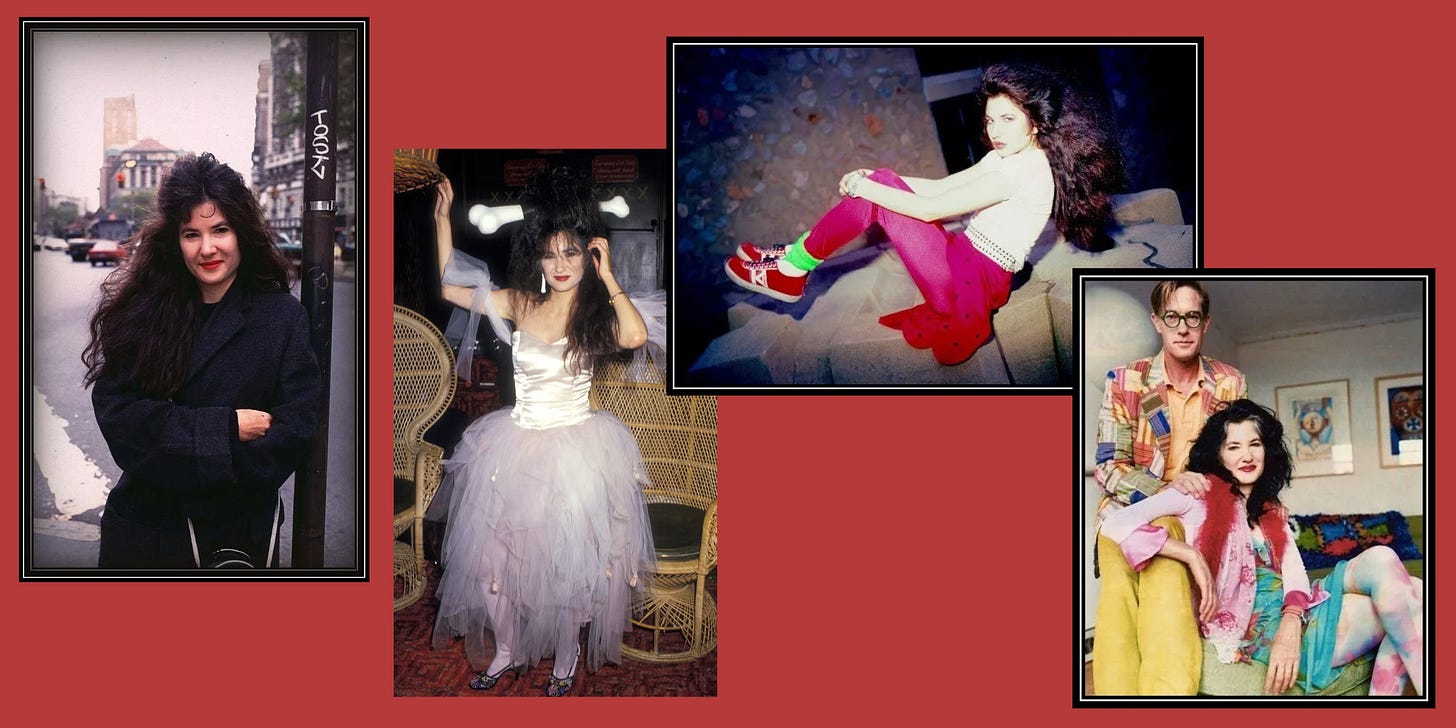

One of the delights of moving through the world as a domestic sensualist is the thrill of the hunt, so—just this time—I’m not going to include any secondhand finds too directly inspired by Laurie Colwin. But just for fun… here are some other (bygone and present) New York literary it girls to take sartorial inspiration from!

And some extended reading on both Didion and Colwin that I’ve enjoyed:

-Laurie Colwin and the Power of Domesticity by Amanda Toronto (Ploughshares)

-In Praise of the Domestic Sensualist: Laurie Colwin at 80 by Mia Manzulli (Literary Hub)

-Laurie Colwin’s Recipe for Being Yourself in the Kitchen by Rachel Syme (The New Yorker)

-My Mother, Myself: To My Mom, Who Wrote For Allure About Parenting Me in 1991 by RF Jurjevics (Allure)

-Joan Didion’s Style Was As Precise As Her Prose by Emilia Petrarca (The Cut)

-'As much about eating as cooking': Anna Jones on Laurie Colwin (The Guardian)

-The Sneaky Subversiveness of Laurie Colwin by Lisa Zeidner (The New York Times)

Ahhh so refreshing. I’m actually new to Laurie Colwin, just read Home Cooking and what a delight. I’ve always found Joan Didion so one note and never really understood the obsession - especially with her personal style. Love love love all these details about Laurie, must read more!

“For me, domestic sensualism means caring about the stories and the origins of everything I own, remembering where things came from, whether that’s clothing or any of my other possessions.”

I love this concept so much. I’m always most captivated by personal style writing that carry this sentiment—it urges me to appreciate what I have and practice my own domestic sensualism, instead of making me covet the next “it” item. Thank you for sharing!