the merch matrix

with a nod to GQ and New York magazine

A GQ article about the “end of merch” by Samuel Hine has been making its way around Substack this past week. While I found it thoughtful and well-written (and more nuanced than the headline, which I know is often not chosen by the writer), there are several parts I’d like to push back on, or at least offer an alternate perspective.

It’s hard to avoid the feeling that all of the merch we’ve collected doesn’t add up to much more than a fuzzy bicoastal identity. When everything became merch, what did any of it mean? When you see other people wearing these specific but ubiquitous signifiers, continues Schlossman, “if anything, you’re thinking, Ugh, I thought I was so smug and special, and here's this other fucking idiot who also thinks they're so smug and special.” Merch once made us feel unique. Then it made us realize that we’re not so unique after all.

One of the best merch-related outfit choices I’ve ever made was wearing my Who? Weekly baseball cap to meet a dogsitter last summer. We introduced ourselves, she bent down to pet my dog, engaged in some surface-level conversation. Then she looked up, clocked my hat, and asked, “Are you a Wholigan?1” The relationship changed immediately—it was no longer shallow or awkwardly transactional. We exchanged numbers, left the app behind (sorry, Rover), and started hanging out when I got back from that trip. We’ve since discovered that in addition to that podcast, we have at least one guilty pleasure subreddit in common and we both read constantly. I don’t know if we would have ever hung out if not for the hat. (As an added bonus, when I told my therapist this story, I found out that she, too, listens to Who? Weekly! She is not big on self-disclosure so this was significant for me!)

There’s ordinary merch—and then there’s the merch that constitutes the one-time hottest trend in fashion. A Yankees hat is the former, a Yankees x MoMA ballcap the latter. The addition of an embroidered MoMA logo on the side of a Yankees hat turns an iconic accessory into a style statement and, more importantly, a vector of taste. The modern merch wave was driven by these collectible signifiers.

The ungenerous approach is to assume that someone wearing merch is proudly advertising a parasocial relationship, that they have substituted an attachment to a brand for a true relationship to the community around it (i.e. a certain coffee shop or restaurant), that they have succumbed to the increasingly pervasive commodification of everyday life, or that they have dared to take the time to obtain a limited edition drop or collaboration. And all of that might be true!

But what I think feels most “cringe” about merch is that wearing it shows that you care about something. Which is not always considered cool or effortless! But anyone who says they’re not trying to signal or represent anything by wearing merch is either lying or decidedly not self-aware. Of course you’re trying to project something. That’s what all clothing does! Conspicuously opting out of certain trends, refusing to wear logos, adopting a uniform—every choice sends a certain signal. It’s very hard to opt out of clothing altogether. (And one might argue that the choice to completely re-orient your life around the freedom to not wear clothing says more about you than any outfit could.)

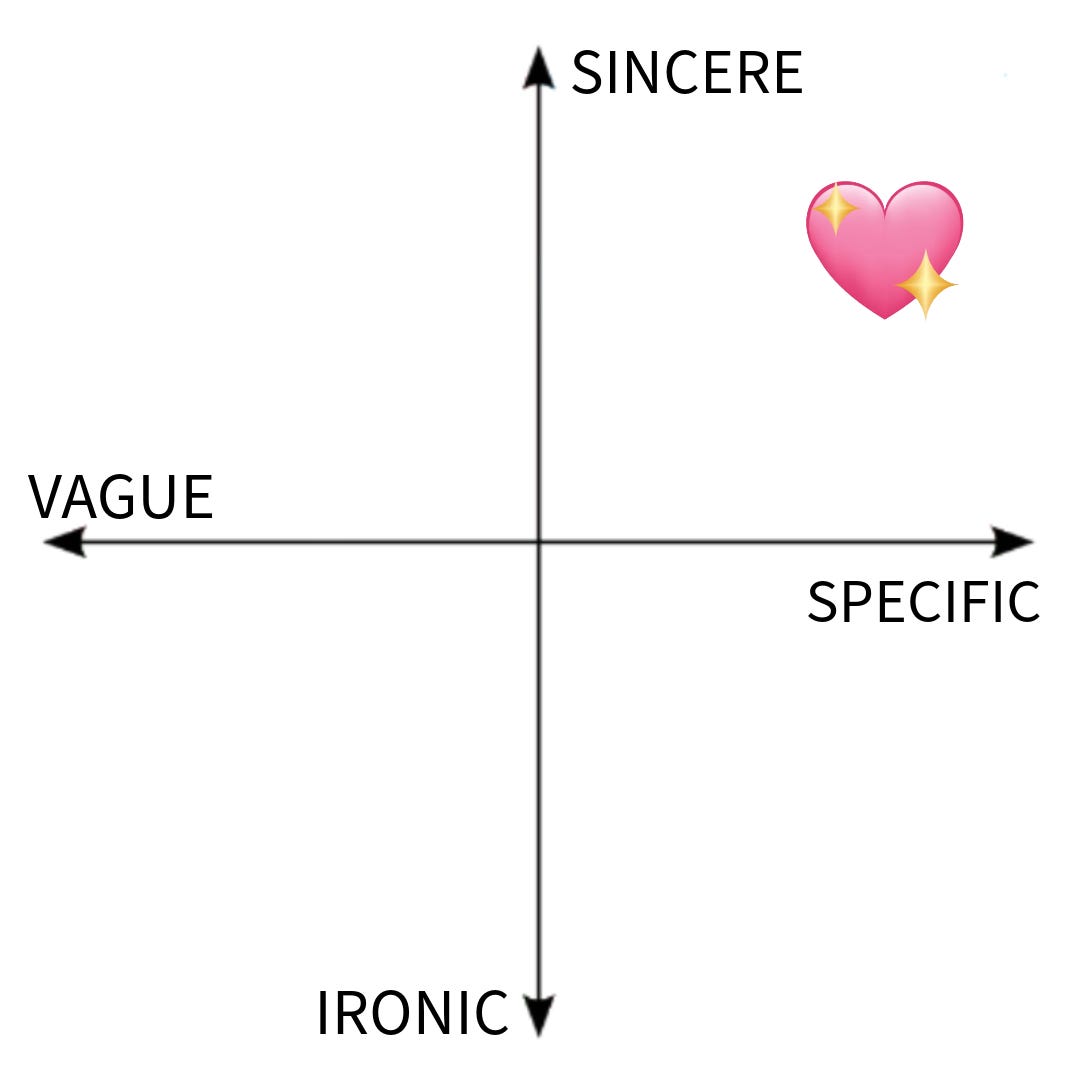

One way to look at merch is on a matrix, à la New York magazine (no stranger to the merch game themselves!)

The x axis moves from vague to specific; the y axis from ironic to sincere.

“Merch used to actually mean something,” says Lawrence Schlossman. “Now, it’s more of a broad-stroke signifier that represents some type of nonspecific message about what you care about. A billboard that says you live in New York or spent two weeks walking around Silver Lake, or whatever.”

I would put that specific type of merch here:

My sweet spot is usually here:

But it’s okay to fall anywhere on this matrix that appeals to you!

In the online age, Funk explains, merch offers a succinct and legible way for people to define themselves. “It’s such an easy way to communicate to strangers, Hey, we might have something to talk about. It is social collateral.” Merch, Funk says, is part of “a conversation that's happening actively everywhere all the time.”

I wear my Jenny Lewis tour t-shirts because I have appreciated her lyricism and talent for two decades now and want everyone to listen to her music. I wear my thrifted Taco Bell shirt because Taco Bell is my favorite chain restaurant and I have never been let down by a Crunchwrap Supreme (

, I am dying to know if you have tried one yet!) I wear my extensive collection of Florida hats and t-shirts because I have such a complex love for my home state, and want people to know that it is more than just a bastion of political repression and men doing crazy things (don’t even get me started on the ‘Florida man’ trope.)Perhaps the most important kind of merch is that which acts as a certain type of cultural signal, one that makes your political views or your identity quite clear. It’s one thing to walk around Los Feliz in a “The future is female” t-shirt from Otherwild (itself a replica of a 1975 shirt from the first women’s bookstore in NYC)—it’s another thing to wear “Abortion is healthcare” across your chest in a state like Florida or Alabama. What feels like virtue-signaling in one community can be both a lifeline and a dangerous gesture in many other places.

As I unfolded the creased garments, I found mementos I had bought as far back in 2017 at concerts, restaurants, and from random people on Instagram, all of which I wore for a while then all but forgot about. It was a stockpile from the years when merch occupied a special cultural position, when graphics were the language of style and fashion embraced souvenirs and novelty. I placed my minor collection into a plastic tub for long-term storage. I can’t imagine getting rid of any of it. But I also can’t really imagine wearing any of it anymore.

I’m glad Hine isn’t getting rid of his merch just yet. In another seven years, I hope he opens up that plastic tub for a welcome dose of nostalgia—another gift, developed over time, that merch can give you. And maybe he’ll find something he wants to bring back into regular rotation.

Some merch may feel played out, a wink held a couple seconds too long or directed at an audience you no longer feel a kinship with. But merch is as relevant and alive as you want it to be!

Any favorite items of merch that you will never get rid of?

<3 E

Yes, this is the name for fans of Who? Weekly!

Last summer I took my dad to a Portland Pickles game (collegiate wood bat baseball) and he bought a tshirt AND a hoodie after the first inning. Merch = unbridled enthusiasm = cringe = love.

You can pry my merch out of my cold dead hands. It is fun to be in another state or country and connect with someone on something they’re wearing.

I am concerned about how some influencers, YouTubers, and podcasts make merch that will likely make its way into a landfill because of the pressure to be a ~brand~ Sometimes when I watch YouTubers do this, it feels like they’re trying to make fetch happen so they can market it.