the unwashed phenomenon

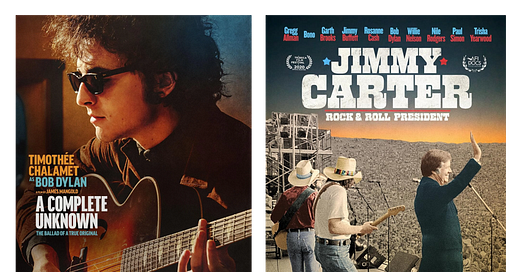

A Complete Unknown, Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President, and mystery and authenticity as two sides of the same coin

My family goes to a movie together each year on Christmas Day. 2024’s pick was A Complete Unknown, the Bob Dylan biopic starring Timothée Chalamet. I like Bob Dylan (though I still maintain that Leonard Cohen was robbed of the 2016 Nobel Prize in Literature), but you don’t have to like Dylan (or Chalamet) to enjoy this movie—in fact, it might be just as enjoyable for those who are firmly Team Baez.1 I left the theater wanting to walk through Washington Square Park on a brisk fall day—hands shoved deep into my pockets, of course—and toss out my entire wardrobe save for a couple pairs of jeans and a leather jacket.

On New Year’s Day, my family watched another movie together—the 2020 documentary Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President. If I was mildly enthusiastic about A Complete Unknown, I am going to lay down the gauntlet here and say that Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President was the best movie I will watch this year. Bob Dylan appears frequently in this movie, too, the real Dylan—much older, voice deeper but still distinctly nasal, more generous with his time. In some ways, Carter was the polar opposite of Dylan (at least the popular conception of Dylan)—thoroughly and publicly devoted to his wife, open about his upbringing and proud of how it shaped him; yet somehow they were able to form a deep and long-lasting friendship. I like to think that Dylan was drawn to Carter not just because of how much Carter enjoyed music, but because of Carter’s ability to be authentic, generous, and vulnerable even from a position of power. For a man so deliberately opaque he wore sunglasses inside the White House, Dylan formed a genuine connection with Carter.

Whether intentional or not, Dylan’s style decisions in those early years at times conveyed a lack of respect, especially once he’s “made it”, the casual nature of his wardrobe signaling a refusal rather than an inability to fit in with a fancier crowd. After his sudden ascent to fame, he wears sunglasses both indoors and out, putting up a wall between him and the general public but also those closest to him, refusing to take them off even during time spent only among friends.

For the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, Dylan picks out a mint green polka dot shirt, a clownish, atypically colorful choice that seems to indicate just how stupid he finds the resistance to his newer music. Sure, I’ll perform, but I’m wearing the clothing of a jester, because that’s how you’ve made me feel. And I’m going electric. Arianne Phillips, the costume designer for A Complete Unknown, clarifies in an interview that Bob Dylan did actually wear a similar shirt during the festival soundcheck. In the movie, Dylan doesn’t end up wearing the shirt to perform, but rather in a pivotal hotel room scene with Pete Seeger, dismissive and childish in response to Seeger’s almost maddening patience.

“The choice for Timmy to wear the shirt in that bed scene wasn’t scripted. Timmy suggested it during rehearsal, and we loved the idea. It wasn’t a carefully considered costume choice—it was just Bob pulling on what was closest to him. But your interpretation of it as clownish, as a precursor to the chaos of the festival, is fascinating. That’s the beauty of filmmaking. These little details take on new layers of meaning through the audience’s perspective.” - Arianne Phillips in an interview for The Art of Costume

Pete Seeger, who acts as Dylan’s mentor throughout much of A Complete Unknown, has much in common with Carter, including a gentle warmth that belies their clarity of vision and depth of conviction. This commonality also came through in their wardrobes. Seeger, even as one of the godfathers of the folk movement, didn’t necessarily fit in with the conception of folk style, appearing more buttoned-up (literally) than his counterculture counterparts, a proto-Mr. Rogers in his cotton sweaters and slacks.2 Seeger sought to give folk music the respect and credit it deserved (if not sanctioned approval)—he didn’t want the way he dressed to take away from or diminish that pursuit.

Despite his familiarity with many of the same musicians of the time, Jimmy Carter also didn’t quite fit in with them—neither rock star nor seasoned politician. Throughout the documentary, we consistently see him in crisp, uncomplicated, plain clothing. (Gregg Allman does share his recollection of encountering Carter shirtless in a pair of beat-up Levi’s at the governor’s mansion, but never in public!3) If Dylan’s aim is to distance and occasionally disrespect, Carter comes off as the opposite—a man of the people, open and accessible.4 He’s game for anything, even mildly embarrassing himself onstage with Dizzy Gillespie, singing the vocals to ‘Salt Peanuts.’ His pants are never too nice to prevent him from sitting on the White House Lawn to enjoy a concert. Carter dresses in a way that welcomes everyone to come as they are, whether that’s Dylan in his sunglasses or Willie Nelson in a tank top and sneakers. And while Bob Dylan’s facial expressions fall somewhere in between a scowl and studiously blank, even in moments of joy or pleasure, Jimmy Carter beams. To make Jimmy Carter happy is to know you’ve made him happy.

Though there were several significant items and outfits from Dylan’s actual past that Phillips faithfully recreated (almost all of the clothing was made for the movie, not sourced vintage, which was fascinating to me!), her approach wasn’t necessarily to replicate piece by piece every documented outfit of Dylan’s during that time period. Instead, Phillips managed to inhabit and convincingly assemble a vibe, something I think is much more difficult to pull off. In sixty-seven outfits, she and Timothée manage to convey Dylan’s dramatic evolution over that four-year period without coming off like a caricature or cheap imitation.

“Our past is a rich source of inspiration,” Carter says in a 1980 campaign speech in Tuscumbia, Alabama. “But the past is not a place to live.”5 At the beginning of what will undoubtedly be yet another divisive and tumultuous year in the course of American and global history, I hope to use these films as inspiration for the future—sartorially and otherwise.

My main takeaways:

It is possible to live a life of service while also taking time for joy. Finding joy—in music and so much more—was such a big part of Jimmy Carter’s life. (Imagine! being the president and still remaining joyful!) In the documentary, Carter’s son even reminisces about the family having no money but his father still scrounging up enough to buy the most expensive stereo system in town. There’s no point in feeling guilty about what brings you joy—turn that energy outward, find a way to share it with the people around you.

I want my clothes to represent who I am, but I don’t want them to overshadow me. As Rachel wrote recently, “Repeating outfits reeks of confidence. It makes something a signature. It says - I know who I am. It feels worldly somehow, knowing.” Having a uniform is more than just a shortcut or a timesaver, it implies that you know yourself well enough to know what else in life gives you purpose and meaning. Seeger, Carter, and Dylan all knew this implicitly, even if their fashion choices weren’t always conscious. Their style played a part in cementing them as the iconoclasts they are.

The title of this post is a nod to a line about Dylan in ‘Diamonds and Rust’. Joan Baez deserves a post of her own—style- and otherwise—not just a throwaway sentence or paragraph in an article about Bob Dylan, which is why I didn’t cover her in this article, but that description of Dylan felt apt here.

Other articles I used for research that weren’t linked or cited in footnotes:

’How Jimmy Carter Used Style to Get His Point Across’ by Isiah Magsino for Town & Country

’70s Music Meets the White House in ‘Jimmy Carter: Rock & Roll President’ by Stephen Deusner for The Bluegrass Situation

‘How the Allman Brothers Band Helped Make Jimmy Carter President’ by Alan Paul for his Substack, Low Down and Dirty

(I’m not a Baez superfan like my friend Haley, but Diamonds and Rust does inevitably make its way into my Spotify Top 100 each year.)

https://www.gq.com/gallery/pete-seeger-musician-style

https://www.heraldtribune.com/story/entertainment/local/2017/05/28/ticket-editor-gregg-allman-jimmy-carter-and-my-favorite-interview-with-rock-legend/20762590007/

After I’d already begun writing this piece, I saw this recent article in The New York Times that essentially makes the same point about Jimmy Carter and authenticity. I’m choosing to include it here because I agree with it, and hope that the rest of my piece sounds distinctive enough that you learn something new from it, too!

https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/tuscumbia-alabama-remarks-campaign-rally-spring-park

“To make Jimmy Carter happy is to know you’ve made him happy.” whyd this bring a tear to my eye lol

This is literally precisely the in-depth article I’ve been dying to read. I love folk music (we listened to Pete Seeger, Dylan, Joan Baez, and Judy Collins nonstop at my extremely progressive elementary school), and the music and values have been a pivotal part of my life. And the Diamonds & Rust reference is perfection.